Spotify Codes are QR-like codes that can be generated to easily share Spotify songs, artists, playlists, and users. I set out to figure out how they worked, which led me on a winding journey through barcode history, patents, packet sniffing, error correction, and Gray tables.

Spotify URIs

Let’s start with Spotify URIs (Uniform Resource Identifiers). Different pieces of media (artists, albums, songs, playlists, users) all have a URI.

The ABBA song “Take a Chance on Me” has this URI:

spotify:track:6vQN2a9QSgWcm74KEZYfDL.

The ABBA Album “The Album” has the following URI:

spotify:album:5GwbPSgiTECzQiE6u7s0ZN

As you can see, the URIs can be broken up into components:

spotify:<media type>:<22 characters>.

The 22 characters are the numbers 0-9, characters a-z and A-Z. This means there are 10 + 26 + 26 = 62 possibilities for each character (almost Base64). So the potential number of Spotify URIs is 62^22 which is equal to 2.7e39 or

2,707,803,647,802,660,400,290,261,537,185,326,956,544

To illustrate that number:

x = 62 ** 22

# the number of milliseconds in a year

x //= 365 * 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000

# the number of words in the bible (about 1 million)

x //= 1000000

If Spotify printed a whole Bible’s worth of URIs every millisecond they could do this for 85,863,890,404,701,306,452,633 years. Safe to say Spotify is not going to run out of URIs anytime soon.

Barcode background

The history of barcodes is quite extensive. Information is encoded into different barcodes in a variety of ways.

A lot of barcodes encode data in the widths of vertical bars. Universal product codes (UPCs) encode 12 digits using combinations of vertical bars of different widths:

Another barcode uses colors to encode data:

QR codes use a 2d matrix of dots to encode data.

A lot of mail barcodes encode data using the height of the bars (like the Intelligent Mail barcode).

Spotify Codes

Spotify codes work like the Intelligent Mail Barcode. Information can be stored in the bars by setting them to different heights.

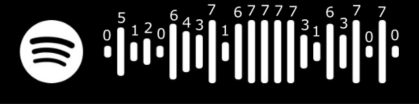

This is the Spotify code for the ABBA song “Take a Chance on Me”:

When the bars are sorted by height you can see that there are 8 discrete heights that they fall into.

This means the data is encoded in octal.

The Spotify logo’s diameter is the same as the height of the highest bar. This makes it easy to generate ratios of the bars’ heights.

In this function I use scikit-image to calculate the sequence of bar heights from a logo.

from skimage import io

from skimage.measure import label, regionprops

from skimage.filters import threshold_otsu

from skimage.color import rgb2gray

def get_heights(filename: str) -> list:

"""Open an image and return a list of the bar heights.

"""

# convert to grayscale, then binary

image = io.imread(filename)

im = rgb2gray(image)

binary_im = im > threshold_otsu(im)

# label connected regions as objects

labeled = label(binary_im)

# get the dimensions and positions of bounding box around objects

bar_dimensions = [r.bbox for r in regionprops(labeled)]

# sort by X

bar_dimensions.sort(key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=False)

# the first object (spotify logo) is the max height of the bars

logo = bar_dimensions[0]

max_height = logo[2] - logo[0]

sequence = []

for bar in bar_dimensions[1:]:

height = bar[2] - bar[0]

ratio = height / max_height

# multiply by 8 to get an octal integer

ratio *= 8

ratio //= 1

# convert to integer (and make 0 based)

sequence.append(int(ratio - 1))

return sequence

This is the sequence of the “Take On Me” Spotify code:

>>> get_heights("/imgs/spotify/spotify_track_6vQN2a9QSgWcm74KEZYfDL.jpg")

[0, 5, 1, 2, 0, 6, 4, 3, 7, 1, 6, 7, 7, 7, 7, 3, 1, 6, 3, 7, 0, 7, 0]

Here are those results overlaid on the barcode:

After looking at a few barcodes, I realized that the first and last bars are always 0, and the 12th bar is always a 7. This must help in identifying if the barcode is valid. Having the 12th bar as the max height also helps you calculate the ratios of the bar heights. I suspect setting the first and last bar set to 0 is an aesthetic choice: it makes the barcode look more like a sound wave. Here are a few barcodes printed out so you can see that the first and last are always equal to 0 and the 12th is equal to 7.

[0, 3, 3, 0, 5, 2, 2, 2, 2, 5, 1, 7, 0, 0, 5, 6, 0, 7, 7, 7, 1, 5, 0]

[0, 5, 6, 5, 3, 5, 4, 2, 7, 2, 5, 7, 1, 3, 1, 1, 6, 1, 1, 6, 7, 6, 0]

[0, 4, 6, 6, 6, 4, 4, 1, 6, 6, 6, 7, 7, 3, 6, 0, 7, 6, 0, 2, 1, 7, 0]

[0, 0, 3, 3, 7, 5, 2, 3, 1, 1, 4, 7, 5, 5, 5, 3, 3, 7, 5, 1, 4, 3, 0]

[0, 6, 2, 2, 1, 5, 2, 6, 2, 2, 3, 7, 7, 6, 6, 4, 5, 6, 0, 1, 4, 3, 0]

[0, 7, 7, 1, 4, 7, 1, 0, 4, 7, 1, 7, 6, 5, 6, 3, 1, 6, 4, 4, 7, 7, 0]

[0, 1, 1, 1, 5, 7, 1, 3, 3, 1, 0, 7, 7, 0, 7, 3, 2, 3, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0]

[0, 7, 6, 6, 7, 4, 4, 6, 7, 0, 6, 7, 0, 4, 1, 7, 3, 2, 0, 5, 4, 7, 0]

[0, 0, 0, 6, 1, 3, 3, 2, 2, 0, 2, 7, 3, 2, 4, 1, 6, 0, 1, 5, 0, 4, 0]

The barcode consists of 23 bars, of which only 20 actually contain information. This means that there are 8^20 pieces of information that can be encoded into the code.

URIs to Barcodes

How do you convert a 63^22 bit URI into an 8^20 bit barcode? There is 2.3e+21 times as much information in the URI than there is in the barcode. This is when I started asking questions and hunting for answers. This question was a start, but I ended up asking this SO question and getting a couple of answers that linked to the relevant patents and contained more info about Spotify’s look up table.

Here is another, more recent patent

“Patents are the worst” - Peter Boone

Let me just say: patents are the worst. They are so dense. I used to think academic papers were full of jargon until I read some technical patents.

The Process

When you visit Spotify codes and input a Spotify URI, a “media reference” is created by Spotify. This media reference is 37 bits long and is the key that links a barcode to a given URI. The media reference may just be the hash of an incrementing index. After extracting a media reference from a barcode, you check with Spotify’s database (a look-up table) to determine what URI it corresponds to. A Stack Overflow user discovered that you can sniff the request that your phone makes when scanning the barcode to determine the media reference and API endpoint.

heights = [0, 2, 6, 7, 1, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0, 4, 7, 1, 7, 3, 4, 2, 7, 5, 6, 5, 6, 0]

media_reference = "67775490487"

uri = "spotify:user:jimmylavallin:playlist:2hXLRTDrNa4rG1XyM0ngT1"

There are a few steps required to turn a media reference into a Spotify code (and vis versa).

Cyclic Redundancy Check

A Cyclic redundancy check is calculated for the media ref. Based on the fact that 8 bits are calculated, I am assuming Spotify uses CRC8.

import crc8

hash = crc8.crc8()

media_ref = 67775490487

ref_bytes = media_ref.to_bytes(5, byteorder="big")

print(ref_bytes)

# b'\x0f\xc7\xbb\xe9\xb7'

hash.update(ref_bytes)

check_bits = hash.digest()

print(check_bits)

# b'\x0c'

Append the crc to the media reference:

media_reference = b'\x0f\xc7\xbb\xe9\xb7\x0c'

Forward error correction

Next forward error correction (FEC) is used to add some redundancy to the code. This makes the decoding process more reliable. Decoding Spotify codes involves going from analog (bar lengths) to digital (media reference), so it is a good candidate for this error correction.

The fundamental principle of [error correction] is to add redundant bits in order to help the decoder to find out the true message that was encoded by the transmitter.

A simple example of error correction would be to replicate each bit twice. So instead of sending 1, you would send 111. When that triplet is sent across a “noisy” communication channel, some of the bits could get flipped. But since there are 2 redundant bits, the receiver can guess what the value was meant to be:

| Triplet received | Interpreted as |

|---|---|

| 000 | 0 (error-free) |

| 001 | 0 |

| 010 | 0 |

| 100 | 0 |

| 111 | 1 (error-free) |

| 110 | 1 |

| 101 | 1 |

| 011 | 1 |

The patents don’t specify what forward error correction schema Spotify uses, but they do say that they add 15 bits at this step. The code rate of an error correction scheme is the ratio of the information bits to the total encoded bit length. Spotify adds 15 bits to the 45 bit code, so the code rate is 45 / 60 = 0.75. This code rate is high (close to 1) meaning it is fairly weak. It facilitates a limited amount of error correction, but that is okay. If you are sending a message to a deep space probe you want a very strong code. A Spotify code is pretty low risk: it’s easy to ping the server a few times if you decode the wrong media reference.

The total forward error corrected code is 60 bits long, which is the exact amount of information that can be encoded in the 20 octals (bar heights) in the Spotify barcode!

The patents do mention that Spotify uses the Viterbi algorithm to decode the media reference from the forward error corrected code. I won’t go into it here, but that algorithm uses the redundant bits from the forward error correction to determine the best guess of the actual media reference.

Gray Code

I really like this part of the Spotify codes.

Gray code is an alternative way to represent a binary number. If you look closely at the following table, you will see that Gray code works by changing only one bit at a time.

| Decimal | Binary | Gray |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 000 | 000 |

| 1 | 001 | 001 |

| 2 | 010 | 011 |

| 3 | 011 | 010 |

| 4 | 100 | 110 |

| 5 | 101 | 111 |

| 6 | 110 | 101 |

| 7 | 111 | 100 |

Why does Spotify use Gray code? What is wrong with normal binary representation of the code?

The difference between 3 and 4 in Gray code is only 1 bit (010 -> 110). In normal binary representation, that difference is 3 bits (100 -> 011). When going from analog (the height of a given bar) to binary, using Gray codes reduces the number of bits that are “wrong” if we calculate the wrong height.

If the height of a bar is supposed to be 3, but we calculate that it is 3.51 and we round up to 4, the binary representation of that number in Gray code will only be off by one bit. This makes the forward error correction more useful.

I think it is cool how Spotify uses “old school” computer science techniques. Frank Gray being concerned about how physical switches operate in 1947 is still applicable today. When you are at the interface between analog and digital, a lot of older concepts become more relevant.

Final thoughts

I was hoping to be able to implement my own Spotify Code to URI tool, but I wasn’t quite able to. I don’t know exactly what forward error correction Spotify uses. I also don’t know for sure if they are using CRC8. There is also another step that I didn’t mention where they shuffle the bars around, and I don’t know how they do that. I haven’t quite given up, though. I plan to spend some more time studying a lot of sequences to see if I can figure out the error detection. I need to generate a bunch of corresponding URI, media reference, and Spotify code triplets.

I didn’t expect to learn quite this much when I started exploring Spotify codes, but that is the cool part about scratching the “curiosity itch”!

Update

Part 2 is out now! You can read it here. In this post I present exactly how Spotify Codes are encoded.